The social determinants of health — the conditions in which a person lives, learns, works, and plays — account for 80 percent of health outcomes, but they’re almost never used in medical care.

“So much affects health outcomes beyond what happens at a medical facility, such as education, access to transportation, financial stability, and more,” says David Haynes, PhD, an Assistant Professor in the Institute of Health Informatics. “Socioeconomic and environmental information is crucial, but it’s not currently captured in patients’ health records.”

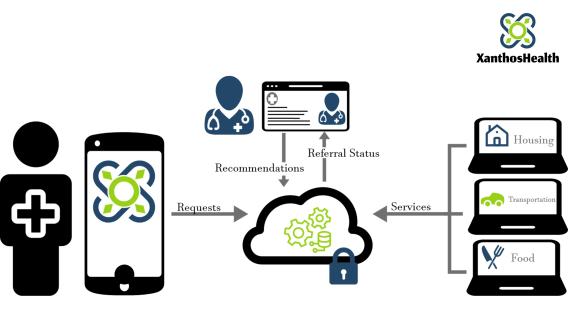

Dr. Haynes is dedicated to changing that. The health geographer is creating a mobile app that better connects patients to social services near them, while integrating key information about a patient’s social determinants of health into their electronic health record.

Called Smart Community Health, the app revolutionizes the way doctors, patients, and community organizations interact, and was developed with support from CTSI’s Pre-K Discovery Scholars Program and Office of Discovery and Translation grant.

Hyperlocal connections

The benefits of Smart Community Health stem from its specificity.

For example, if a patient is facing housing insecurity, they can use the app to find the nearest emergency housing organization and see if they have space available. They can also see if they qualify for assistance, fill out an application, and communicate directly with the organization.

“Oftentimes, people who become food or housing insecure don’t know how to find help, so they end up in the healthcare system,” Dr. Haynes said. “Clinics and social workers typically provide information about social services via handouts that quickly become out of date or don’t include all the information a patient needs. We’re flipping the script by matching a patient’s need to what’s available near them right now.”

Real-time connections

The app’s real-time nature is made possible by allowing community organizations, like emergency housing services or benefits enrollment programs, to update their services and connect directly with patients.

Accurate information helps patients make better choices, and means they aren’t wasting time or bus fare showing up to closed offices or empty food shelves.

Organizations can also communicate with healthcare providers about a patient’s needs in a secure, compliant way. This can lead to better health outcomes, explains Dr. Haynes:

“If a patient is struggling with food insecurity, a clinician can use the app to recommend local food shelves and connect directly with the community organization, such as to say the patient needs a low-sodium diet.”

Better data, better medicine

In addition, Smart Community Health helps optimize patient care by giving providers a clearer picture of a patient’s overall health.

“Doctors usually have detailed information about a patient’s personal health history, but only a minimal understanding of their environment,” Dr. Haynes explains. “Our app changes that by integrating social determinants of health right into a patients’ electronic health record. Doctors can see how often their patient faces food insecurity or whether or not they have a car, which can make a big difference in whether they can make it to specific locations for treatment.”

Information is gleaned from the way patients use the app, such as what services they request. This is far more precise than, say, inferring one’s social determinants of health based on zip code.

Improving care

Smart Community Health helps clinicians too. They can quickly identify a patients’ non-medical needs, more effectively connect them to social services to help, and even develop more effective treatment plans.

“The app gives clinicians a better sense of whether the patient actually goes to the organization they recommended,” says Dr. Haynes. “If you’re sharing recommendations via paper handouts, you almost never know this.”

Dr. Haynes is even more excited about the big-picture potential:

“Generally, a doctor’s recommendation carries a lot of weight among patients. If the app leads to more people using the services that can help them, I’d call that a big win. It’s a seemingly small step that goes a long way toward improving both quality of life and overall health.”

A neighborhood approach to health

Smart Community Health grew out of work Dr. Haynes began at the Minnesota Department of Health.

As a newly minted PhD, he helped the agency determine how many uninsured and underinsured Minnesota women would be eligible for free breast cancer screenings. Using spatial analysis methods, Dr. Haynes discovered which neighborhoods were underrepresented in the screenings, allowing the program to reach residents more effectively.

In his second postdoc appointment, at the University of Minnesota, Dr. Haynes employed similar analyses to advance the understanding of lung cancer disparities in different communities.

A colleague then suggested he apply for an Early Career Research Award (ECRA) — an initiative from CTSI and the Medical School used to recruit and support early-career research faculty who are underrepresented in medicine. He was accepted, making him a tenure-track faculty member at the University and giving him a unique opportunity to expand his work.

“I pivoted toward helping people gain access to care more generally,” he says. “With the funding and protected time from ECRA, I built a simple beta version of Smart Community Health.”

Benefits, multiplied

ECRA scholars also become part of CTSI’s Pre-K Discovery Scholars Program, a career development program that provides training, mentorship, and research funds to early-career faculty. Dr. Haynes credits the program with arming him with critical skills for taking both his career and the app to the next level, saying:

“CTSI’s Pre-K program helped me in so many ways, professionally and personally. When you're conducting research, you can feel like you’re on an island by yourself. The program showed me that wasn’t the case.”

In addition, he says he learned how to more effectively balance his work life, write grants, and pull in people around him.

“Perhaps the most beneficial part was learning how to ask for help effectively,” says Dr. Haynes. “Senior researchers told us we were going to need help and that we should know how to ask for it.”

Personal and professional growth

The way Dr. Haynes grew as a person in the Pre-K program promises to serve him well through the rest of his career.

“I developed thicker skin,” he says. “I learned how to use criticism to improve my work, along with effective strategies for navigating sticking points. For example, if I face an obstacle like a paper that’s not getting accepted, I have a better sense of how to move that forward.”

Dr. Haynes may be early in his career, but it’s taking off quickly. He’s secured grants and been appointed a leadership position on CTSI’s informatics team, managing efforts related to geospatial analytics and health equity informatics.

Putting knowledge to use

While in the Pre-K program, Dr. Haynes met Pinar Karaca-Mandic, PhD, a Professor with the Carlson School of Management. Together, they applied for a grant from CTSI’s Office of Discovery and Translation to advance Smart Community Health and position it for commercialization.

Funding, expert guidance, and project management support enabled them to finish coding the app and begin piloting it.

“Thanks to CTSI, we could pilot the app — one of our most significant milestones so far,” he said. “We learned so much, and it was incredibly rewarding to see clinical teams, community organizations, and patients buy into the concept and root for its success.”

Since then, Dr. Haynes and Karaca-Mandic created a start-up company, XanthosHealth, and have secured an NIH Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) Phase 1 award through which they are on a path to commercialize the app.

Changing the future of healthcare

Once Smart Community Health hits the app store, Dr. Haynes hopes it will give healthcare providers more data and lead to new — and better — ways to treat patients.

“We’re on a mission to improve health outcomes by factoring social determinants of health into the care approach,” he said. “When non-medical needs are identified and addressed early on, it improves both clinical care and quality of life.”