Researchers from the University of Minnesota and community are expanding upon work done during the Immigrant Microbiome Project that was partially funded by CTSI in 2015. The project identified changes in gut microbiomes in Southeast Asia immigrant and refugee populations, specifically Hmong and Karen women, to potentially uncover why there is a shift or decline in people’s health once they’re living in the United States.

The project was led by Pajau Vangay, PhD, MS; Dan Knights, PhD, Associate Professor of Computer Science and Engineering with a joint appointment in the BioTechnology Institute; and Kathleen Culhane-Pera, MD, Medical Director of Quality and founding member of Somali, Latino, and Hmong Partnership for Health and Wellness (SoLaHmo) at Minnesota Community Care. At the time of the initial study, Vangay was a Ph.D. student in Knights’ lab with a background in computer science and food microbiology; she is currently a science policy postdoctoral fellow with the California Council on Science and Technology.

Together, they looked at the possibility that changes in the composition of the gut microbiome go hand-in-hand with living in a westernized location and a change in lifestyle.

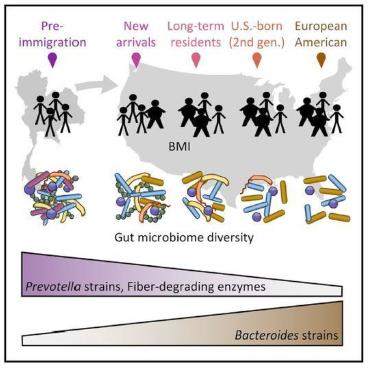

“[During our study], we found that immigrants begin losing their native microbes almost immediately after arriving in the U.S. and then acquire alien microbes that are more common in European-American people,” said Knights, the senior author published in the scientific journal Cell. “But the new microbes aren’t enough to compensate for the loss of the native microbes, so we see a big overall loss of diversity.”

He continued, “When you move to a new country, you pick up a new microbiome. And that’s changing not just what species of microbes you have, but also what enzymes they carry, which may affect what kinds of food you can digest and how your diet interacts with your health.”

The pilot cross-sectional study compared the microbiome of Hmong and Karen immigrant women in Thailand and in Minnesota, who have been in the U.S. for varying lengths of time and have varying body sizes. An additional mouse study was designed to evaluate how diets could affect the gut microbiome. Ultimately, they hope to conduct a longitudinal cohort study of newly arrived immigrants to understand how the microbiome changes the longer someone lives in the U.S.

A collaboration was born

Minnesota was the perfect location to start the study, as it is home to many large immigrant communities. After moving to the Twin Cities, Vangay, who is Hmong, developed connections with community leaders as well as with Culhane-Pera and Shannon Pergament, MPH, MSW, Co-Director of Community Based Research and founding member of SoLaHmo.

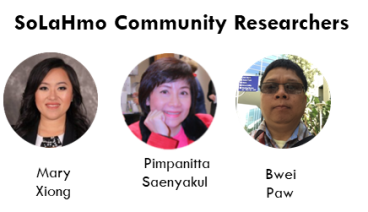

Working together as a community-academic partnership, Vangay, Culhane-Pera, Pergament and SoLaHmo community researchers Mary Xiong, Bwei Paw and Rodolfo Batres ultimately chose this project as a worthwhile opportunity to gain much-needed answers for immigrant communities and applied for funding.

“[We hear] people say ‘we thought we were coming to the United States to be healthier and instead we’re sicker,” said Culhane-Pera. “We had to get to the bottom of it.”

The three investigators and researchers from SoLaHmo chose to concentrate on research with the Hmong and Karen communities, as those communities had the most availability and interest in the project. The team was determined to find answers to some of the communities’ most top concerns, which include obesity, diabetes, and other chronic diseases.

Community participation key in bringing results

CTSI’s Community Health Collaborative Pilot Grant Program, which is managed by CTSI’s Office of Community Engagement to Advance Research and Community Health (CEARCH), supports community-university pilot research projects that address important health issues identified by Minnesota communities and aims to stimulate high-impact research that leads to health improvements. The study utilized a community-based participatory action research (CBPAR) approach where researchers worked with members of the Hmong and Karen communities in both Minnesota and Thailand to help design the study, recruit participants, and educate communities about the findings.

“It was fascinating to implement CBPAR principles in a bench science project, and then to use the findings and outcomes to impact those community members’ lives,” said Pergament, Co-Director of Community-based Research at MCC and founding member of SoLaHmo.

Because it was CBPAR, SoLaHmo researchers were vital members of this egalitarian research team. They brought their unique community and cultural expertise to the table, and forged bonds with Knights and Vangay to carry outSoLaHmo Community Researchers pictured left to right: Mary Xiong, Pimpanitta Saenyakul and Bwei Paw. key functions in the research process and contributed to making decisions throughout the project.

“CBPAR allowed me as a community researcher to fully understand the research, and created a great relationship with researchers and trust with the University, as well as ownership of the research because the community was involved,” said Xiong.

Networking was a main component of recruiting participants, as researchers needed participants not just from communities in Minnesota but also Thailand. Community advisory boards brought in representatives of the communities to shape the research.

Crossing barriers while gaining a community’s trust

Vangay and SoLaHmo researchers often had to get creative to find their study participants. “We would find ways to connect with newly arrived immigrants, go to community and church events, build connections with those at Neighborhood House, and Karen Organization of Minnesota,” said Culhane-Pera. “We really wanted to go where people gather beyond those first arrivals and meet the next generation.”

It was inevitable that barriers would occur, and the researchers tried to prevent them from happening as much as possible by identifying potential issues.

“We knew [Hmong and Karen community members] would wonder, ‘what do you want? why do you want it? what’s in it for me?’” said Culhane-Pera. “We needed to go deeper to find out what motivated people. We needed to address their needs or desires.”

They started by listening to the community’s concerns about their health. The communities shared that a whole generation had gained weight, became obese, and had higher levels of diabetes and blood pressure. The community researchers explained that by participating in the study, community members would be key in identifying what changes happen to immigrants’ intestines when they arrive in the U.S. and possibly identify if those changes could be connected to obesity and development of chronic diseases. Additionally, if the study could determine why the changes are happening, people could potentially avoid or counteract the changes, which could possibly help them prevent obesity and chronic diseases.

Gaining trust was important to enroll people in the study, and to obtain and study fecal matter from women in both Minnesota and Thailand communities. Community researchers needed to learn how to talk with prospective participants about stool, how it impacts the body and what ‘microbiomes’ are.

“Community connections became powerful, as well as explaining the importance of what researchers were doing for their communities,” Pergament said.

It was imperative for the community researchers to have a clear understanding of the research to help recruit participants and answer questions, as well as discuss potential correlations with lifestyle changes and chronic diseases, such as dietary changes and obesity.

“I explained that was what we hoped to research…that we knew something was changing about their lifestyle and the foods they ate. It opened up a lot of conversations about food and cultural food ingredients. It helped provide a purpose as to why this project was important,” said Xiong.

Other barriers the team experienced included how to best explain the project to Hmong and Thai speakers, as certain English words are not translatable to their native language. Additionally, some participants had concerns about participating in research due to traumatic experiences with health care and research in the past.

The project’s next steps on the horizon

“We owe the [initial] success of the project to the community researchers who worked so diligently recruiting participants through their connections with the community,” said Knights. “They were also able to provide us with a wide range of ages in participants as well, which was very important to the outcome of the study.”

An important next step is understanding which changes are contributing to obesity and other emerging diseases, such as heart disease and diabetes, after the immigrants get to the U.S. Knights said they also want to deepen their partnership with the Hmong and Karen communities, and SoLaHmo researchers, and look forward to getting their input on what they want to learn next.

“We will be using a combination of animal models and more human studies to gain a better understanding of which factors of industrialized society are most influential in causing changes to the microbiome and subsequently to obesity and/or diabetes,” Knights said.

Study receives more funding for the continuation of research

In addition to being supported by CTSI’s National Institutes of Health’s National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences grant UL1TR002494, the research was also supported by the University of Minnesota Healthy Foods, Healthy Lives Institute, the University of Minnesota Office of Diversity, and the University of Minnesota’s Graduate School.

The project has also received follow-on funding from the Minnesota Partnership for Biotechnology and Medical Genomics (MNP) to gain insight into how one’s metabolism changes after immigration, and implement dietary therapies in local immigrant populations to curb obesity rates. MNP is a partnership between the University, Mayo Clinic and the state of Minnesota. Its combined goal is to exchange knowledge, resources, and expertise to advance health care and scientific discoveries for all Minnesotans.

CTSI’s Office of Discovery and Translation (ODAT) department also partners with MNP and Mayo Clinic for its Translational Product Development Fund (TPDF). In fact, Knights, accompanied by his co-principal investigators, applied for and received funding in the past through CTSI’s TPDF, in which the researchers developed CoreBiome, a technology company that provides microbiome analysis using cutting-edge genomics and informatics. He also applied for and received funding through CTSI’s Biomedical Informatics and Data Access (BPIC) program in 2015 for gut microbiome.

"The funding I have received from CTSI has been critical in advancing my microbiome studies and research for the health and well-being of immigrant and non-immigrant Minnesotans alike," said Knights.