From the outside, it looked like a Zumba class. Smiling women in headscarves clapped and danced while upbeat music blared. Scattered among them were University of Minnesota researchers and community healthcare workers, jamming along.

If this doesn’t sound like a typical science-focused community event, well, that’s the point. This is exactly how Mickey Eder, PhD, an Assistant Professor with the Department of Family Medicine and Community Health, wants it.

As part of CTSI’s Science Café project funded by NIH’s National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Dr. Eder has been reimagining how institutions can better connect with immigrant and refugee communities about health issues.

A model adjustment

Science Cafés have long brought together scientists and the general public to talk about topics like healthcare and wellbeing. Their unique structure eschews the standard lecture model in favor of lively conversations in casual settings.

“Science Cafés are a proven way to engage with the general public on health issues, but they hadn’t been used to reach immigrant and refugee communities,” Dr. Eder said. “Our research discovered that, with a few modifications and a lot of hard work, Science Cafés are effective for these communities too — a critical insight since they face some of the largest barriers to healthcare.”

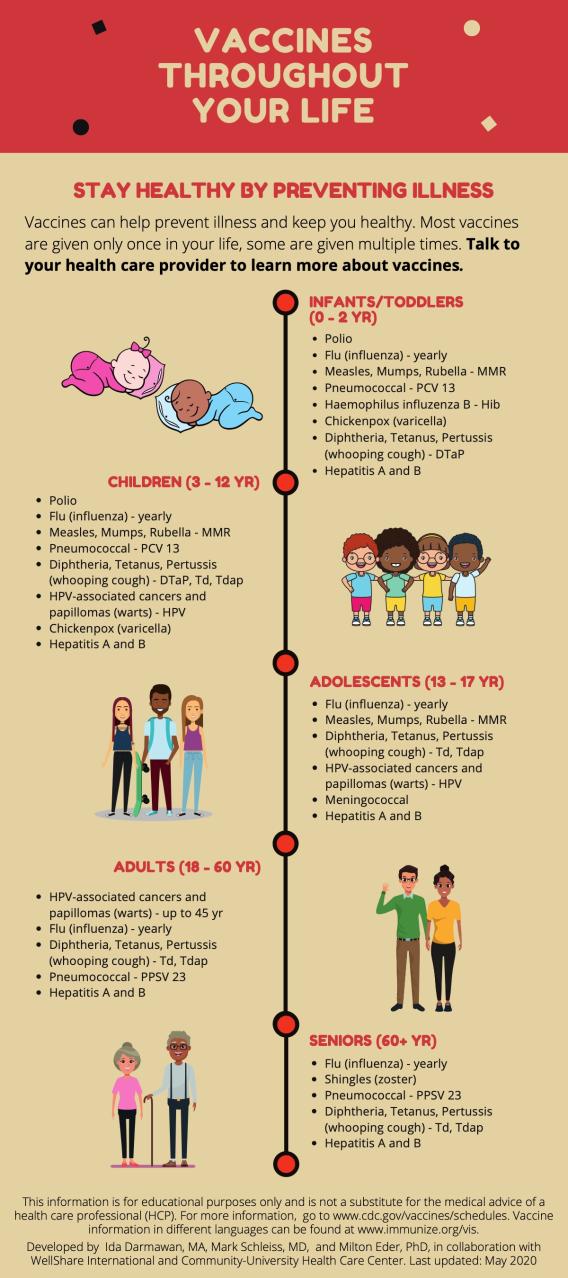

The finding stems from a multi-year effort to partner with Minneapolis’ Karen, Somali, and Spanish language communities to hold 18 Science Cafés on health topics ranging from vaccinations and exercise to navigating the healthcare system. The team prepared material on a topic of interest to many communities, and then worked with interpreters to engage communities across languages and cultures in discussions.

Approaching with humility

From the beginning, Dr. Eder knew he would need fresh ideas to create Science Cafés that could benefit these communities. The majority of attendees spoke no English at home, plus each culture carries different expectations around healthcare, social gatherings, and outsider knowledge.

Dr. Eder pulled in a diverse and multilingual team of academics, experts, and community healthcare workers, and the team got to work adapting the Science Café model for immigrant and refugee communities.

Among them was Siobhan McMahon, PhD, RN, an Associate Professor at the School of Nursing and former CTSI KL2 Scholar who helped design and lead Science Cafés focused on exercise and movement.

“Cultural humility was key,” she said. “Each Science Café went in different directions because we let the community lead the way. During conversations with the Somali community about ways to stay physically active, they eventually said, ‘Let’s just do it through dance’ — so that’s what we did. We broke out a boombox and danced for 20 minutes.”

Bending the rules

The traditional Science Café model is built around a premise of removing anything that could reinforce a lopsided power dynamic between expert and audience. This applies to settings (never formal or academic), presentations (no slides, no podiums), and attitude (always informal).

But Dr. Eder and team knew reaching a new kind of audience would mean revisiting these assumptions. They focused on doing whatever they could to make the material more accessible to each audience.

Changes ranged from not covering taboo topics like mental health to breaking the no-slide rule so they could better reach people who weren’t comfortable with reading. An artist created illustrations and animations that conveyed key points in an inclusive way.

“We avoided photography completely. We didn’t want attendees to see people who don’t look like them and don’t dress like them, and incorrectly think the message doesn’t apply to them,” Dr. Eder explained. “To illustrate that the information was for everyone, we created visuals representing a wide range of people, some donning headscarves and others wearing shorts.”

This approach also came in handy when the pandemic forced Science Cafés to go online. The team then adapted their aesthetic to create short, animated videos for introducing topics and starting conversations.

What’s lost in translation

Language was a key challenge and a central focus of the team’s work.

Not only were they trying to impart complicated information about subjects like vaccines, they also needed to confront educational barriers. Most attendees received no more than a few years of school-based education.

“It’s not as simple as relying on a translator because translators are often much more highly educated than the people they are translating for,” said Dr. Eder. “A traditional approach to translation may contribute to barriers faced in clinical settings — even if a translator or translated materials are available, most aren't able to truly grasp what's being conveyed.”

To avoid linguistic hiccups, the team worked to “decenter” English in their materials before talking with the immigrant communities. The researchers, translators, and community members teamed up to reflect on and refine the way they talked about each concept, striving to go beyond direct translations to clear, understandable prose.

Trust as a byproduct

A paper about the team’s Science Café effort, published in the Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, details one success. Utilizing a Medical College of Wisconsin approach to Science Café assessment, over 80 percent of attendees said they made positive gains in their understanding of each topic, and a smaller majority said they better understand the idea of research on the topic and how scientists or doctors use research. Essentially, Science Cafés armed people with practical knowledge that they could take action on.

But statistics don’t tell the complete story.

“By talking about health issues in a way that reflects the daily life and experiences of each community, we opened the door to genuine conversations and ultimately built trust,” says Dr. Eder. “Trust is a byproduct of effective communication.”

Talks also uncovered opportunities to directly respond to community needs. At a vaccine-focused Science Café in the Karen community, an attendee mentioned their neighborhood had never hosted a flu shot clinic. So, one of the event’s University collaborators — Mark Schleiss, MD, a Professor with the Department of Pediatrics — set up a clinic that gave flu shots to 26 people, many of them children and elderly.

Lasting impact

Importantly, the events also helped community members find new ways to help one another.

At a different Karen Science Café, the group discussed different ways to enter the healthcare system, such as going to a primary care provider, an urgent care facility, or an emergency room. Those who had been to an urgent care facility shared their experience with those who had never heard of it.

“Instead of relying on the ‘expert’ in the room, they began talking to one another about their own experiences in their native language,” says Dr. Eder. “The language barrier actually created new opportunities for peer-to-peer learning and set the stage for sharing health experiences with one another.”

Dr. Eder encourages other institutions to adopt the Science Café approach, noting approach’s substantial potential for long-term impact:

“By sparking authentic conversations about health issues, we’re taking a critical first step toward lasting change.”

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health’s National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, grants UL1TR002494 and KL2TR002492. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health’s National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences.