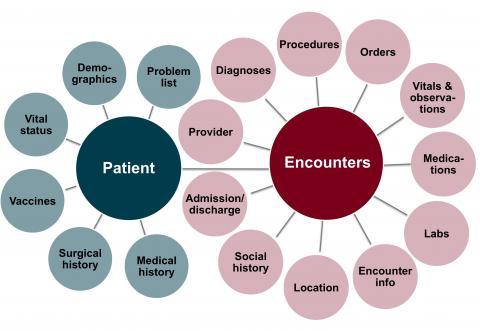

Researchers can securely utilize the electronic health records of more than 2 million de-identified patients, thanks to a clinical data repository created by the University of Minnesota’s Clinical and Translational Science Institute (CTSI). The information-rich resource gives researchers unprecedented ability to study medical conditions, analyze patient outcomes, and pinpoint best practices across large populations, all while protecting patients’ privacy.

Gyorgy Simon, PhD, an affiliate faculty member at the University, exemplifies how this clinical data is opening up entirely new pathways for discovery.

One of Dr. Simon’s most ambitious projects to-date uses CTSI-supplied clinical data to uncover how diseases like diabetes and hypertension progress. The project was recently awarded a $1 million R01 grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and could ultimately help improve the way patients with those conditions are treated and cared for.

“The research I’m doing would not be possible in the age of paper medical charts, and would not be possible without the clinical data from CTSI,” says Dr. Simon, an Associate Consultant at Mayo Clinic and an affiliate faculty member at the University of Minnesota’s Institute for Health Informatics, which celebrated its 50th year of informatics at the University of Minnesota in 2015. “By creating access to these electronic health records, CTSI helped me secure an R01 grant and advance knowledge about a critical health issue.”

Requesting the data

It all began with a desire to conduct exploratory research about diabetes, a disease that affects nearly 10 percent of Americans, according to a 2014 report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Dr. Simon, whose research focuses on mining data to solve problems in medicine, had been analyzing electronic health records from Mayo Clinic, and wanted an additional data source to cross-reference his findings. He engaged CTSI’s Informatics Consulting Service, which helped him retrieve the records he needed from the University’s clinical data repository.

Dr. Simon’s data request, like the research he wanted to conduct, was comprehensive and highly complex. Given the exploratory nature of his research, he sought data about any patient with any indication of diabetes or prediabetes at any time.

“What’s great about working with CTSI’s Informatics Consulting Service is that I can tell them what I’m trying to do at a high-level, and count on them to fill in the details and ultimately deliver the data,” says Dr. Simon. “They’re knowledgeable, dedicated, and utterly reliable.”

For example, he says he didn’t have to worry about laboratory codes, something he said he wouldn’t have been able to do anyway. The CTSI team handled that part, pulling records that listed any sign of either diabetes or prediabetes. This ranged from elevated sugar levels to an actual diagnosis to a related complication, with each record going into greater detail about lab results, diagnoses, medications, dates, and more.

While Dr. Simon is an accomplished informatics expert, CTSI’s Informatics Consulting Service also helps those with little or no informatics experience leverage clinical data for their own research.

Painting a holistic picture

Dr. Simon quickly realized that combining the results from the dataset provided by CTSI with the one from Mayo Clinic could offer the best of both worlds.

The University’s clinical data repository provides a huge volume of data, with the records of more than two million Fairview Health Services patients seen at eight hospitals and more than 40 clinics. Mayo Clinic’s data, on the other hand, was exceptionally clean and complete, covering 100,000 de-identified patients with long follow-up and who didn’t go elsewhere for care.

After analyzing the data, Dr. Simon and one of his collaborators, Kevin Peterson, MD, MPH, of the University’s Department of Family Medicine and Community Health decided to focus on the area that’s least understood clinically: the trajectory of how diabetes, hypertension, and related conditions progress.

While scientists know that someone who develops diabetes is more susceptible to a range of other metabolic conditions, not as much is known about the underlying disease mechanism and how it develops over time. The idea behind Dr. Simon’s research is that, by finding patterns in the sequence of various metabolic conditions, one can better understand the underlying mechanism of the diseases and potentially predict the direction it will go in.

This kind of knowledge could open new doors for treatment, as Dr. Simon explains:

“We know that diabetes, hypertension, kidney conditions, and cardiac diseases are all related, yet they’re treated in isolation. Mining electronic health records could change the way we approach care, and create a future where patients can be treated comprehensively.”

Piloting their approach

To demonstrate that the study could in fact be feasible, Dr. Simon conducted a pilot study using the clinical data from CTSI and Mayo Clinic.

The study examined the relationship between statin use and diabetes, and identified risk and protective factors previously not clearly defined.

The results suggested that people with multiple at-risk traits associated with diabetes differ in terms of how susceptible they are to related disorders, and how they respond to the treatments used to treat co-existing conditions. Findings were published by the American Medical Informatics Association.

While these findings are preliminary and have yet to be validated, they shed light on the kinds of insights that could be uncovered by better understanding the trajectory of diabetes.

Securing federal funding

Dr. Simon leveraged this study along with the data supplied by CTSI and Mayo Clinic for an even bigger win: An R01 from NIH. The award will provide $250,000 annually for four years.

For this project, Dr. Simon and team will stitch results from the two clinical datasets together. This will allow them to analyze the data as a whole, reconstruct the progression patterns of metabolic diseases, refine their methodology, and validate their findings.

“The data supplied by CTSI enabled us to get a million-dollar R01 grant,” says Dr. Simon. “One of the most significant aspects of our grant proposal is the way we’re combining the two datasets to get a holistic look at the progression of diabetes, and validate what we find. If there are true patterns about the way disease develops and how people respond to treatments, we’d expect to see that on both sides.”

The large volume of the Fairview dataset set enables Dr. Simon and team to validate findings from a statistical perspective, while the Mayo data’s long follow-up times allows them to validate findings from a clinical perspective. They’ll use the Fairview clinical data to closely examine individual sections of the progression, while the Mayo clinical data will act as the scaffolding for reconstructing the progression patterns and viewing the two datasets together.

A multi-site collaboration

The melding of the University of Minnesota and Mayo Clinic goes beyond the electronic health records used for the research. Dr. Simon’s R01 team pulls knowledge from both institutions and from various areas of expertise.

Collaborator Dr. Kevin Peterson has experience stitching datasets together and with diabetes specifically, while Dr. Michael Steinbach from the University’s Department of Computer Science and Engineering handles the data mining aspect of the project.

The team’s clinical knowledge comes from two Mayo Clinic physicians: M. Regina Castro, MD, an endocrinologist provides the team with diabetes expertise, and Pedro Caraballo, MD, a leader in clinical decision support helps ensure findings can be actionable from that perspective.

And of course, there’s Dr. Simon, who leads the informatics aspect of the research. This particular project is in the early stages, but to Dr. Simon, the future of using electronic health records for this kind of research is bright:

“By harnessing the power of computers, we can understand the underlying patterns of disease, and support physicians so medicine isn’t limited to what a human can remember."